The City of Cape Town will soon start a unique pilot project which will allow three domestic households to feed their excess electricity, created from renewable energy sources, back into the city´s grid.

The project will run on a net metering basis without any actual financial transaction taking place. Instead, the households will receive one free unit of electricity for each unit fed into the grid.

A project of this nature has never been attempted before in South Africa.

One of the participants is retiree Dr Anthony Keen, formerly with the University of Cape Town’s medical school, who has made renewable energy solutions for his household a lifelong passion.

According to Keen the exact arrangement with the city still needs to be finalised.

“The pilot project is in its early days and policy is still being developed as we go along,” he says. “I guess it will run for about a year with careful monitoring to enable the City to develop and test policies carefully.”

The initiative’s eventual aim is to bring many more such connections on board. Keen believes this could be arranged through a metering system which measures the energy exchange and which will allocate an equivalent number of units to the contributors from time to time.

It has taken Keen three years to get to this point with the city as certain conditions needed to be fulfilled. Most important was getting permission from power utility Eskom to export energy into the grid.

Grid operators often have legitimate concerns about the safety of the domestic system and the quality of the power being generated. These aspects are covered by regulations which the household first has to fulfil, usually a long and involved process, says Keen.

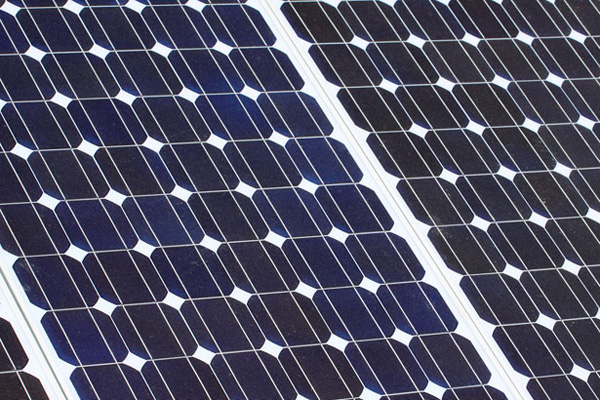

Energy from the renewable source, in this case his house, is fed through an inverter to change it to mains type power for use on the premises. Grid-tied inverters, designed to be linked to the grid, are also available. These devices are generally expensive.

South Africa is also developing new regulations for domestic and small commercial renewable energy systems of less than 100 kW in capacity, said Keen.

Off-grid household

Keen embarked on his off-grid journey 28 years ago. He believes that in general South Africans are not energy conscious enough as electricity is still far too cheap in the country.

Yet simple measures can make a remarkable difference, from replacing incandescent bulbs with energy efficient lighting, to being more aware about the consumption going on in your house.

This includes switching off so-called vampire appliances such as mobile chargers, DVD players and computers which consume energy while not in use.

Keen recently gave a lecture on how to take a house off-grid to members of the South African National Energy Association, a non-profit organisation focusing on promoting the sustainable supply and use of energy.

In 2011 he was Keen was a finalist in the organisation’s Energy Project Award programme.

Solar water heating makes a big difference

According to Keen, the most far-reaching energy change a household can make is by installing solar water heating. This is an expensive initial outlay which can be achieved with the help of an Eskom subsidy or adding the cost to your home´s bond, but it will pay for itself within a few years.

Keen bought his solar water heater 28 years ago, and has never needed to maintain or replace it. He recouped the cost of this investment after six years. The lifespan of a panel is about 25 years.

He advises households wishing to reduce their electricity bill to start small, first with one photovoltaic panel, and gradually build up a renewable energy portfolio.

At his own home he installed 20 photovoltaic panels with a total output of 3.8 kWh, a 6 kVA inverter and a lead acid battery bank of 24 two-volt batteries.

To take a house completely off-grid, a large bank of storage batteries is required. New age lithium batteries are the answer and are becoming available for domestic use although they’re still quite expensive, while the lead/acid batteries are inefficient and take up more space.

In the end, says Keen, taking your house off-grid requires a large degree of “over-design” with considerable excess energy available at times. For example, enough solar panels must be installed to cover household energy needs in winter, meaning in summer almost half of the generated energy will be in excess – this could be fed back into the grid.

This is what Keen has been working towards and why he’s excited about the latest Cape Town project.

“Being able to receive compensation for excess production by net metering or a feed-in-tariff is very handy to utilise the full potential output of your system.”

Eskom estimates that a solar water heater can save approximately 200 kWh per month of the 1 100 kWh an average home uses, and the entire investment can be recouped within seven years.

Helping households to save electricity

Eskom has started a new energy efficiency programme for homeowners – the residential mass roll-out. Through it, Eskom will install certain energy saving technologies free of charge in targeted areas.

A bouquet of efficient technologies is available, among them geyser blankets and hot water pipe insulation, compact fluorescent lights (CFLs), special shower heads, and regulators and geyser controllers.

So far, Eskom has fitted 43-million CFLs in homes across the country, saving 1 800 MW of electricity as a result, the equivalent of half a power station. CFLs give off the same amount of light as standard incandescent lights, but use just 20% of their electricity.

The programme is scheduled to run until 2015.

Farming with hydroelectricity

Norman Collett, owner of Grassridge Farm between Cradock and Middelburg in the Eastern Cape, says his home has never been connected to the national grid.

Instead, for the last 30 years or so the Colletts have made use of hydroelectricity generated from turbines in the nearby Brak River.

Collet´s late father was the initial trailblazer of hydraulic power on the farm when he installed a single turbine, which serviced the houses on the farm.

In the 30 years that it was in operation, there was just one year when electricity was in short supply, as a result of drought, says Collett.

With farming needs increasing and water becoming scarcer, Collett had to rethink the whole setup and decided to upgrade the now dated turbine system with three locally manufactured turbines able to generate three-phase power.

A project which took almost four years to complete, he had to rebuild the sluice walls, install new sluice gates and finally, in 2010, installed two one-ton turbines, with a third added in 2011.

Producing 52 kWh of electricity, the three turbines provide power to three households on the farm, seven staff quarters, the farm workshop and the major user of power, the farm’s centre pivot irrigation system.

Despite the heavy load, the turbines still produce more power than the farm uses, with about 20 kWh going to waste, says Collett.

“There is so much renewable energy available in this country. We should be more pro-active in our approach to energy.”

Words by Emily van Rijswijck via Media Club South Africa

Image via here