Words by Janine Erasmus

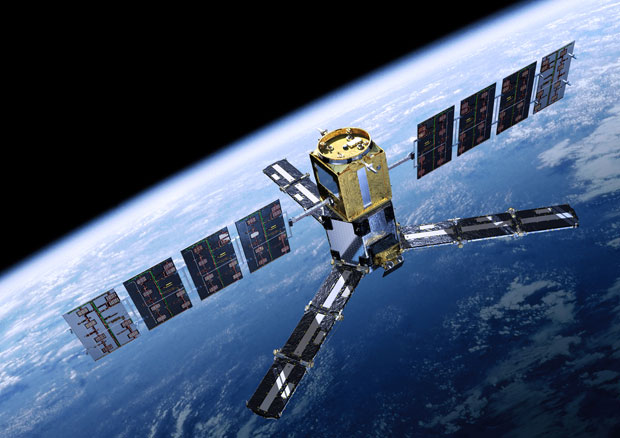

The science of earth observation (EO) is gaining ground in South Africa. It gives us a new perspective on our planet, helps us understand our environment, and uses satellite information to anticipate climate variations such as drought or floods.

This was the message at the Space Science Colloquium that took place at the University of Pretoria (UP) in early October. Organised by the Japanese embassy in South Africa, along with the national Department of Science and Technology (DST), the event brought scientists from the two countries together to discuss the latest developments in EO, micro-satellites and astronomy.

The colloquium was co-hosted by the Nairobi Research Station of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, and supported by South Africa’s National Research Foundation. Its theme was Promoting Space Exploration and Earth Observation: Contribution of Japan and South Africa to Humanity.

The event coincided with the first day of World Space Week, which was first held in 1999 and celebrates its 13th anniversary in 2012. It takes place every year from 4 to 10 October and this year is held under the theme Space for Human Safety and Security.

EO can also help in assessing water quality through the mapping of eutrophication – the excessive growth of plant matter on a water surface when nutrients are present in abundance, often because of the addition of chemicals – as well as fire scar mapping and damage assessment:

Another use for EO is to detect change in land use, for instance the growth of informal settlements, and uncover other crucial information that could affect the ecology of an area or the safety of residents. For instance, if the settlement is built on agricultural land or wetlands, or is located near or under electricity pylons, the people and fauna and flora could be at risk.

Other EO applications that have a benefit for society are disaster response and management, atmospheric pollution observation, and the monitoring of deforestation.

Learning from the experts

In the last 80 years Japan’s space industry has come along in leaps and bounds, said former science and technology minister Naledi Pandor, speaking at her last engagement in that position, and South Africa can learn much from the Asian island nation.

“We have good relations with Japan, our most important commercial partner in Asia,” she said in her opening address. “They are working with us in areas such as biotechnology, information technology, the development of manufacturing technology capacity, renewable energy, and the development of capacity in space.”

These are key areas into which the DST invests its resources, added Pandor.

“The Japanese government pays particular attention to three key areas – funding of basic research, strong university partnerships, and strong protection of intellectual rights,” she said. “We are attempting to follow suit, to learn from them.”

South Africa’s funding of basic research has grown in the last decade and the country recently established an agency to protect university intellectual property.

“We’ve learned a lot from Japan but we can still learn more,” said Pandor. “We need to focus more strongly on university and private sector partnerships if we want to make the most of opportunities.”

She named the relationship between industry and universities as a massive opportunity for entrepreneurship and job creation, and added that South Africa has to make better use of the transfer of technology contracts, as well as the expiry of drug patents, to create more opportunities.

“We are lucky to have a competent core of scientists who are world-class in technology and innovation, so the base is there,” Pandor said. “Our scientists achieve very well and hold good rankings in the international arena, but we need to grow the ability to commercialise the intellectual property they produce.”

South Africa has to work faster to accelerate this commercialisation, she said – if not, it will always be the client of others.

Imaging for the good of mankind

Climate change specialist Dr Jane Olwoch, MD of the South African National Space Agency’s (Sansa) earth observation division, said that satellite imagery helps people to understand the current situation in terms of land use and degradation.

Sansa has a number of operational themes in its EO programme, including environmental and resource management, disaster management, industrial activities, and urban planning and development.

Based at Hartebeeshoek, west of Pretoria and Johannesburg, the core business of Sansa’s EO division is data reception and processing, image archiving, dissemination of information, and development of applications.

Satellite information is received at Hartebeeshoek, explained Olwoch, and once it is processed by a bank of 14 dual and quad core processors, it is archived in an 80-terabyte online catalogue, with older data held in a 760-terabyte tape library.

The archive goes back to 1972 and is a rich resource, she said, holding, among other data, about 1 900 images captured by the now-defunct SumbandilaSat, South Africa’s second commercial satellite. These are available at no charge.

Sansa EO is also responsible for the redistribution of imagery from other sources such as the Ikonos EO satellite and TerraSAR-X – these, however, are not free.

“We want more people to access our data, and understand what we can derive from it,” Olwoch said. The catalogue is available online at http://catalogue-sansa.org.za

Keeping an eye out from the sky

Dr Waldo Kleynhans, a senior researcher at the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research’s remote sensing research unit (RSRU), is one of a team of experts that is developing EO applications for South Africa.

Two of these projects involve the detection of anthropogenic – man-made, caused by humans – land cover change, and maritime domain awareness, involving the monitoring of South Africa’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ) and territorial waters.

In the first instance, said Kleynhans, the objective of the RSRU project was to develop a change alarm that is able to detect the formation of new settlements and can accurately distinguish between the spread of settlements and natural cycles.

“Human settlement expansion is the most pervasive form of land cover change in South Africa,” said Kleynhans.

However, to ensure accurate readings, a bi-temporal approach is not always appropriate. This refers to readings that are taken only twice. For example, the land may become drier in winter but a computer, given only a summer and winter reading, will interpret the natural event as a change.

“The temporal frequency should be high enough to distinguish change events from natural cycles such as the seasons.”

The change alarm program uses Nasa’s moderate-resolution imaging spectroradiometer on board the Terra and Aqua satellite platforms, which covers the earth every two days or so and delivers images with a resolution of 500 metres – this is the dimension of each pixel in the image.

The data are analysed using two change detection methods, both developed by the local team. They are the extended Kalman filter change detection method, and the autocorrelation change detection method.

Moving on to the maritime application, Kleynhans named piracy, illegal fishing and oil spills as a few of the potential problems in South Africa’s maritime domain. Monitoring is currently achieved predominantly through transponder-based systems such as satellite automatic identification or long-range identification and tracking, as well as terrestrial-based radar systems such as those situated in Simon’s Town, the seat of the South African navy.

“Terrestrial based radar systems are effective but only cover a fraction of South Africa’s total EEZ, which extends over 1.5-million square kilometres,” said Kleynhans. “South Africa has more sea than land to monitor, because the land area is just over 1.2-million square kilometres.”

Satellite data and newer technologies such as synthetic aperture radar, he said, play an important role in monitoring this extensive piece of ocean, which includes the area along the coast and also that around the Prince Edward Islands – Marion Island and Prince Edward Island – situated some 1 800km southeast of Port Elizabeth in the Eastern Cape.

Synthetic aperture radar (SAR) is used mostly from the air, from an aircraft or satellite, and uses the flight path of the platform to electronically simulate a large antenna or aperture. The captured information is then used to generate high-resolution remote sensing imagery.

SAR is viewed as a potential addition to current maritime monitoring efforts, said Kleynhans, and using the technology, thousands of square kilometres can be surveyed in a single overpass.

An international collaboration between bodies such as Pretoria University and the US office of naval research has yielded a system known as the International Collaborative Development for Enhanced Maritime Domain Awareness.

“It’s an open source platform,” said Kleynhans, “which everyone can use. We are one of five countries contributing to the database.”

The program and web portal is under development by researchers in Chile, Ghana, the Seychelles, South Africa and Mauritius. It provides information that can be freely accessed and analysed by the global maritime community on issues such as wave detection and oil spills.

UP’s contribution focuses mostly on vessel detection. Even if a ship switches off its transponder, said Kleynhans, the program will still be able to detect it and in fact, disabling a transponder is often a cue to illegal activity, meaning that the relevant naval or coastal authorities can be alerted in time.

“With historic vessel location information, intent detection algorithms are currently being researched, with particular emphasis on illegal fishing and piracy,” he said.