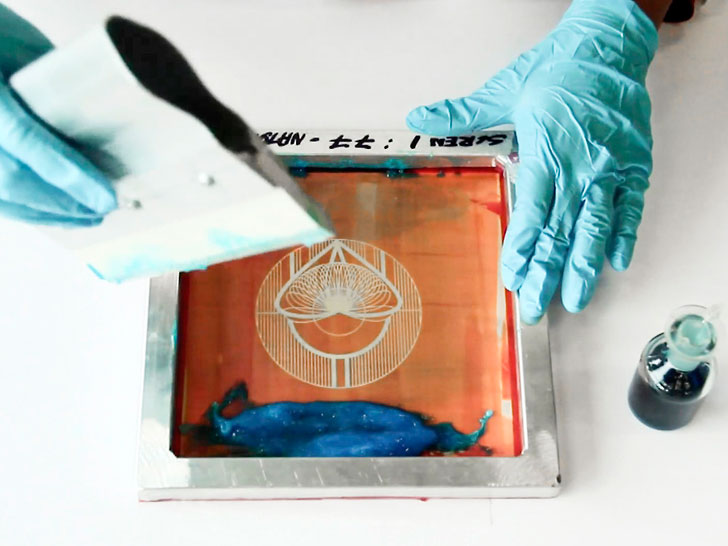

London-based “design futurist”, Natsai Audrey Chiezais is the prime mover behind “Faber Futures,” the first line of screen-printed textiles to use microbes, commonly found in soil, as as dye machinery.

According to a recent post on Ecouterre, Chiezais together with University College London’s John Ward, “train” bacteria to create a range of pigments as a byproduct of their metabolic activity. The trick, Chieza says, is to manipulate the composition of their nutrition. Organisms cultured from the roots of tarragon, for instance, create different results than inoculations from rosemary or mint. Changes in incubation temperature, pH levels, and growth period can also generate shifts in hue.

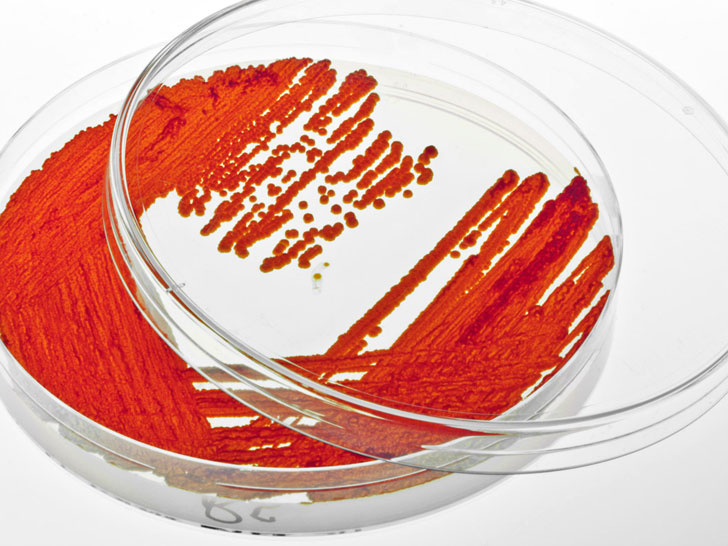

Chieza uses resistance dyeing to realise her designs. There are a few key differences, however. Instead of dye vats, petri dishes bear swatches of origami-folded habotai silk. And rather than yield an immediate outcome, stains morph over time as the bacteria-secreted pigments diffuse through the myriad layers.

“Long after the peak of microbial activity is reached, a fine silk palimpsest serves as a record of what it was to live, then die, in seven days,” Chieza writes on her website.

Faber Futures, she says, doesn’t just embody a “new age” of emerging craft practice that incorporates molecular biology, but it also demonstrates the potential of using living organisms to create less-environmentally damaging materials and protocols.

“The project is driven by the theory that harnessing living systems—from biomimicry to synthetic biology—could lead to a more resilient future,” she adds.

Chieza’s ultimate goal is to pin down a library of reproducible colors, with an eye toward scaling up her methodology.

Source: Ecouterre